Photo: Great American Rail Trail / courtesy of Rails-to-Trails Conservancy

Harnik rightfully deserves credit for being one of the pioneers who led a movement that positively affected the lives of millions of Americans. His book will be a reference for trail designers and builders for generations to come.

Chuck A. Flink, FASLA, is an award-winning author and landscape architect. He is the author of The Greenway Imperative: Connecting Communities and Landscapes for a Sustainable Future, University Press of Florida, 2020.

The History of the Rails-to-Trails Movement

By Charles A. Flink

https://dirt.asla.org/2021/07/06/the-history-of-the-rails-to-trails-movement/

Peter Harnik’s From Rails-to-Trails: The Making of America’s Active Transportation Network explores the interwoven history of American railways and the rails-to-trails movement. As Harnik declares at the outset, “you can’t have a rail-trail if you don’t have an old railroad line.” An oversimplification? Yes. But as Harnik further outlines, rails-to-trail projects are far more complex than pulling up abandoned railroad tracks and converting the rail bed into a walking and bicycling corridor.

Why and how Americans decided to convert abandoned rails to active transportation trail corridors cannot be easily explained. Nearly half of From Rails-to-Trails is devoted to the fascinating history of America’s railroads — why and how they were established; why there were so many different rail corridors; and why thousands of miles of track were later abandoned. The gold rush nature of railroad development generated a glut of duplicative rail lines and associated train service, which after World War II was pared back to match changing needs, culture, and transportation preferences.

Harnik offers the backstory of why Americans demanded outdoor linear-oriented recreation and alternative transportation and then transformed seemingly worthless strips of land into a network of local, regional, and national hiking and biking corridors. He describes the politics behind the rails-to-trail movement, specifically the contributions of public servants, unsung heroes, and forgotten contributors who enabled the movement to succeed. According to Harnik, “the conversion of abandoned rail lines to trails wasn’t a Great Society–type program that came out of a mandate from Washington, D.C. It was an up-from-the-grassroots movement that bubbled out of modest places like Sparta, Wisconsin; Maywood, Illinois; and Rochester, Minnesota.”

From Rails-to-Trails is packed with an incredible array of charts and supporting data that explain all the twists and turns that led Americans to transform 18,000 miles of abandoned railroad into trails. His book is well researched and documented, and the writing style is clean and crisp, and appropriately punctuated with wit and humor.

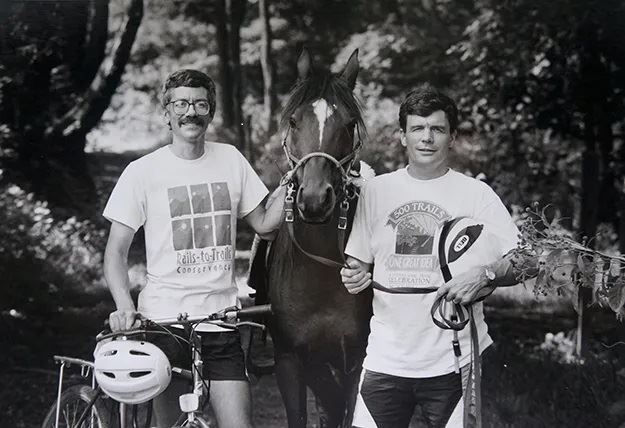

Harnik, along with David Burwell co-founded the Rails-to-Trails Conservancy, an organization that was born out of necessity and came of age during increased railroad abandonment and renewed national interest in non-motorized transportation.

Photo: Peter Harnik (left) and David Burwell (right) / Robert Trippett

Harnik shares a personal story of bicycling in Manhattan in the 1960’s and longing for landscapes that would be car free and dedicated to non-motorized travel. He describes his early fascination with trains and admits that it took him fifty years to connect the dots and fully appreciate how much he loved both modes of transportation. Harnik’s passion for trains and bicycling is evident as one winds through his marvelous account of how railroads were transformed into trails.

From Rails-to-Trails then answers some of the most important questions about the conversion of abandoned railroad corridors:

Why were there so many railroad corridors in the first place? Harnik recounts that “an extended railroad fever took hold from 1830 to 1890 (nearly 60 years of railroad construction), interrupted only by periodic panics and depressions. And in this environment, companies with the best endpoints, the loudest promoters, and the best connected political lobbyists (and bribe distributors) fared best.” He states that a railroad corridor, unlike a highway corridor, is difficult to share and therefore each track represented a unique economic opportunity. Some popular markets, such as St. Louis and Chicago, were served by numerous independent operators, all of which laid their own railroad.

Photo: Pennsylvania Railroad Meyersdale train / courtesy of Bill Metzger collection

What caused Americans to abandon rails? Simply put, America’s romance and love of train travel changed dramatically after World War II. Formerly frequent users of rail service were “waylaid by shiny new government funded highways and airports. Shippers were increasingly choosing trucks, short distance passengers were using cars, and long-distance travelers were rapidly shifting to airplanes.” Railroads began failing at an alarming rate; an economic reckoning was at hand.

How did rail-banking come about and why has it been such an effective strategy for conserving abandoned rail corridors? Harnik profiles a group of young lawyers, lobbyists, and real estate specialists whose combined talents resulted in the creation of a special “bank” designed to receive unique “deposits” of abandoned railroads. “If they were in a bank, they wouldn’t be officially abandoned but could be saved for the future.”

How did the rails-to-trails movement get started and why was the Rails-to-Trails Conservancy a key leader in this movement? Converting rails-to-trails began slowly with a few signature projects developed in random locations across the nation, such as the Elroy-Sparta Trail in Wisconsin, the Burke-Gillman Trail in Seattle, and the Cedar Valley Nature Trail in Iowa.

The movement was born through the dogged determination of a few brave souls who used ingenuity, grit, and determination to rescue abandoned railroads before they were lost forever. The perfect storm of abandoned railroads occurred on November 30, 1981, creating the need for a national non-profit organization to emerge and begin to address the catastrophic collapse of the railroad industry.

Burwell and Harnik were in the right place at the right time, with aligned interests and a passion to challenge the status quo. Harnik reflects “when I first heard about rails-to-trails, I was electrified to discover a type of corridor that had never been sullied by the tread of a tire. Giving no thought to any legal niceties or pitfalls, I immediately set out to publicize that, yes, there was something new under the sun.”

Photo: Georgetown Branch B&O railroad track (overhead) became the Capital Crescent Trail / Peter Harnik

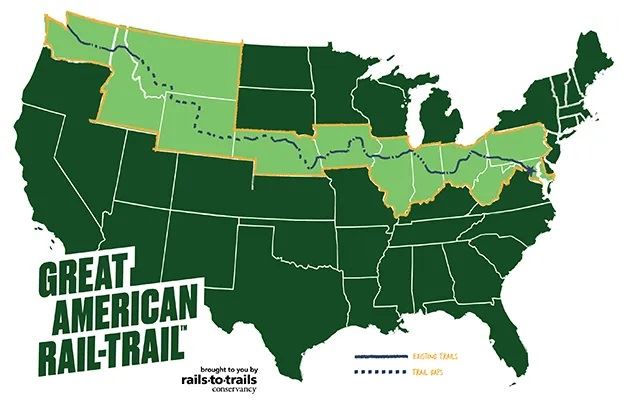

The final chapters of the book offer a glimpse into the long-term value of rails-to-trails as the framework for an interconnected, coast-to-coast, non-motorized transportation network capable of satisfying America’s insatiable desire for travel and recreation. Harnik describes how the rails-to-trails movement has matured and evolved to become one of the most important land conservation and real estate enterprises in American history.

With more than 18,000 miles of rail-trails in existence, rails-to-trails surpasses the combined mileage of the Appalachian Trail, Pacific Crest Trail, and all other national scenic trails. The rails-to-trails movement has forever changed the way in which Americans use trails. Many of the nation’s most popular and heavily used trails are rail-to-trail conversions.

Harnik doesn’t highlight the contributions of any one profession in From Rails-to-Trails. But it is worth noting the contributions landscape architects have made in furthering the movement. Landscape architects led efforts to formulate design guidelines and construction standards for converted rail-to-trails and have consistently led multi-disciplinary teams in the design and development of the most notable rail-to-trail projects in the nation.